In Towards a physical interpretation of MOND's a0, I arrive at the conclusion that, maybe, a0=cH/2 has a better basis than the more commonly quoted a0≈cH/2π. In the process of doing so, I call upon the value G.

It should be noted that Milgrom makes this statement:

A0 is the “scale invariant” gravitational constant that replaces G in the deep-MOND limit. … a0≡A0/G (…) delineat(es) the boundary between the G-controlled standard dynamics and the A0-controlled deep-MOND limit.

He also talks in terms of “departures”:

relativity departing from Newtonian dynamics for speeds near the speed of light

and

quantum theory departing from classical physics for values

of the action of order or smaller than ℏ

and

a sweeping departure from standard (ed. ie Newtonian) dynamics at low accelerations

It seems to me that, at least in my derivation, there’s an issue with using G that way, I am using a situation where there is a borderline acceleration namely gravity that would manifest at the surface of a black hole with the [critical] density of our universe such that gU=a0, which is dependant on a specific value of G. Note also that G is, in a sense, already scale invariant. It has a value of unity, unless one departs from natural units (such as Planck units) and instead uses arbitrary units (such as SI units).

Note that my problem is not with a0, but more with the idea of this variable gravitational constant.

As Sabine Hossenfelder notes (before noting that MOND “doesn’t work” [her quotation marks]), MOND does a nice job of explaining the why outermost stars of a spiral galaxy orbit faster than the mass of the galaxy alone in a Newtonian regime would permit. But I don’t think we need to fiddle with G to get there.

---

Getting back to “departures”, it’s unclear precisely how Milgrom means the term, but listening to Pavel Kroupa, a proponent of MOND and the author of The dark matter crisis: falsification of the current standard model of cosmology, there are those working on MOND who see it as more benign. Newtonian mechanics are perfectly good for working out how the solar system works. Until you notice small perturbations in the orbit of Mercury and General Relativity is needed. General Relativity is just a better approximation of how things work, it’s not that Newtonian mechanics are wrong. You can (and, if you want to get things done, should) ignore Einstein if you are considering slow moving things in regions of constant, relatively low gravity and just use Newton. But you could use Einstein.

I suspect that the same thing is going to happen with MOND. Whatever equation eventually falls out of the work (the “deeper physics” as Kroupa puts it), it should be the case that that equation can be used in both “regimes”, Newtonian and (deep-)MOND.

---

According to Angus et al. there is an interpolating function μ(x), such that for x<<1, μ(x)=x, and for x>>1, μ(x)=1 where μ(g/a0)g=gN (and thus μ(g/a0) =gN/g). Note that gN is Newtonian gravity due just to baryons while g is the observed, “overall” gravity.

The standard interpolating function used to fit to rotation curves is μ(x)=x/√(1+x2). This can also be expressed as μ(x)=1/√(1/x2+1). And putting it to use where x=g/a0, we get μ(g/a0)=1/√( /a02/g2+1)=gN/g.

The comment made in the linked paper is that “there is a considerable body of evidence that the galactic mass profiles of baryonic and dark matter are not uncorrelated”. The authors tagged this as “curious”, but what I find curious is that they say “not uncorrelated” rather than saying “correlated”. The reason, if I understand it correctly, is that the correlation is back to front. With the standard interpolating function as given (and even more so in the replacement version that the authors suggest), one can only calculate the effect of baryonic matter (the actual matter that we know exists and isn’t merely theoretical) if you know the “overall” mass profile (including an overwhelming quantity of dark matter). You can’t, in any simple way, start off with so much baryonic matter and work out that we have this much dark matter.

I don’t like this.

---

Let us instead say that gravitation due to an ordinary baryonic mass M at any radius r is given by:

g = GM/r2+√(GMa0)/r = gN+√(GMa0/r2) = gN+√(gNa0)

The consequence of this is that both terms will diminish as the radius r increases, with the former dominating until its value approaches a0. As r increases beyond that point, the latter term will begin to dominate.

Putting this into similar terms as above (parameterising the correlation and specifying the implied interpolating function):

μ(a0/gN)gN=g where μ(x)=1+√x, so that where a0<<gN, g=gN and where a0>>gN, g=√(gNa0).

Personally, I don’t think this makes things much clearer, although I do realise that the relationship is not immediately obvious from the first equation above.

---

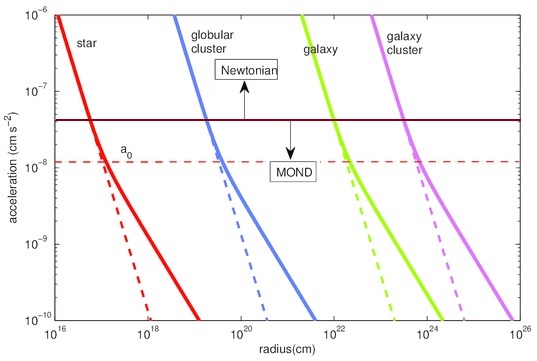

When this correlation is charted for four types of mass, a star, a globular cluster, a galaxy and a galaxy cluster (using the same masses as used by Milgrom, see below), we get this (where a0=cH/2):

Compare this with Milgrom’s chart (where a0=1.2×10-10m/s2=1.2×10-8cm/s2, a star is one solar mass, the globular cluster is 100,000 solar masses, a galaxy is 30 billion solar masses [at the very low end of the mass of the Milky Way in terms of known baryonic matter only] and galaxy cluster is 30 trillion solar masses):

I tried to regenerate this my own way, to use Milgrom’s version of a0, while using the more common m rather than cm, but I get this:

Note that the departure from the Newtonian regime begins much earlier and is greater in magnitude in the transition range (which is basically what is shown).

I can overlay the two

charts using different values for a0:

The effect due to using a different value of a0 appears to be marginal. However, it should not be forgotten that the axes here are using a logarithmic scale. It should also not be forgotten what MOND (and dark matter) is being postulated to explain.

Consider a spiral galaxy, like our Milky Way:

What astronomers observed is that stars in the outer arms are going faster than could otherwise be expected given the mass of the galaxy. So, either there is extra mass in the galaxy that we can’t detect (dark matter) or there is some gravitational effect that we don’t fully understand (MOND).

Strictly speaking, you don’t have one mass orbiting another mass, they both orbit the centre of their combined masses, but when one is vastly greater than the other, we consider the larger to be the one being orbited by the other. In that case, we can consider a smaller mass to have an orbital velocity around the larger mass, M, such that the acceleration towards the centre is balanced by the centripetal force outwards, normally:

F=ma=GMm/r2=mv2/r

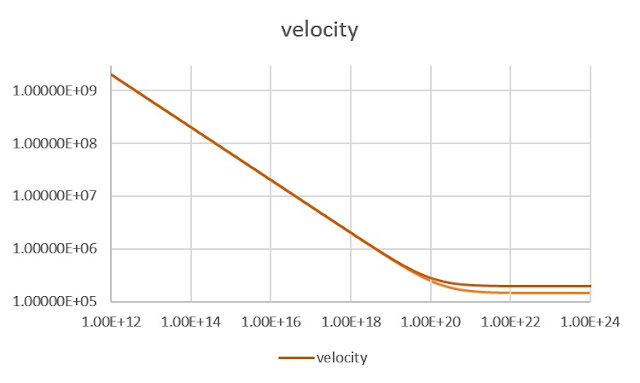

Such that v=√(a.r)=√(GM/r). What we can do now is calculate the effect of MOND (where a0=ch/2) on the orbital velocities. Since the curves are similar for stars, galaxies, etc, we can just use a galaxy.

Note that once we get out to about 10,000 light years from the galactic core, the orbital velocity is basically constant from then on out. The Milky Way is 100,000 light years across.

Once we have calculated the orbital velocity, we can

consider the quantity of mass required in a Newtonian regime to have that

orbital velocity at the relevant radius, using Meff=rv2/G,

as a proportion of the actual mass of the galaxy (notionally 30 billion solar

masses, or 6×1040kg):

Now this doesn’t look like much, but again, remember that this is a logarithmic scale. The darker mass curve is mine, representing MOND with an a0=cH/2. The delta is, once they level out, consistently such that the effective mass is in the order of 77.25% higher than with a0=cH/2π.

Note that Milgrom states “For galaxy clusters, MOND reduces greatly the observed mass discrepancy: from a factor of ∼10, required by standard dynamics, to a factor of about 2.” Using my alternate version of a0, this residual discrepancy seems to disappear.

---

Applying this to our solar system, which is orbiting the galactic core at about 250 km/s, or v=230,000m/s, at a radius of about 26,000ly, or about r=2.5×1020m, and assuming H=71 (equating to the universe being 13.77 billion years old) … this would imply that, if a0=cH/2, the mass of the galaxy is about 30 billion solar masses, or M=6.0×1040kg. To get the same figure orbital velocity at the same distance from the galactic core using the assumption of dark matter, the mass would be about 100 billion solar masses, or M=2.0×1041kg. If a0=cH/2π then, it’d be about 60 billion solar masses, or 1.2×1041kg.

It appears that these are at the very low end of the range for the mass of the Milky Way, particularly the 30 billion solar masses figure, given that there are some recent estimates that it might be in the order of a trillion solar masses (including dark matter). However, I have checked and rechecked the figures and that’s what pops out. Also, this is just the mass within the orbit of our solar system. We are 26,000 light years from the core, but the Milky Way galaxy is about 100,000 light years across, so some fraction of the mass does not contribute to our orbit around the galactic core, whatever is in the 24,000 light year ring about the sphere defined by our orbit. This is probably less than a third of the entire mass though (remembering that there’s a super massive black hole at the centre):

It also seems to be what Milgrom arrived at, since he had his galactic mass as 30 billion solar masses and it’s not difficult to assume that he did so, because that’s precisely what is required to have our solar system orbiting the galactic core at 230,000m/s – however, this would be if he was using a0=cH/2 rather than a0=cH/2π. Use of the latter would imply, as indicated above, a galactic mass of closer to 60 billion solar masses and it would be odd of Milgrom to have not used that, especially since he indicates an “observed mass discrepancy” at a factor of 2.

---

There are two other calculations worth looking at, that for the Earth’s orbit around our star, and the value of gravity at the Earth’s surface.

The Earth has an elliptical orbit at an average radius of 1.496×1011m from the centre of the Sun, which (unsurprisingly) has a mass of one solar mass, or about 2×1030kg. Using all three methods (pure Newtonian, my MOND and Milgrom’s MOND), the results were within 0.015% of 29,789m/s (when using 1.9891×1030kg as the solar mass). The accepted average orbital velocity is 29,783m/s.

It should come as no surprise that the value of gravity at the Earth’s surface is also largely unaffected by introducing MOND calculations. The Earth’s mass is 5.97×1024kg and sea level is at 6.37×106m on average. In all three methods, the result is 9.82m/s2, with the MOND related contribution being a negligible 0.00059% or 0.00033% for a0=cH/2 and a0=cH/2π respectively.

---

TLDR:

A potentially better variation of MOND is one in which g=GM/r2+√(GMa0)/r

where a0=cH/2. The

rotation curves work, the mass discrepancy raised by Milgrom disappears and there

is a physical understanding behind the value of a0.

.jpg)

.jpg)