John Hawthorne recently gave a presentation

on fine-tuning from Bayesian perspective to the Royal Institute of Philosophy’s

Religious Epistemology Conference. It’s

basically the same presentation as given a couple of years ago, but with a different conclusion.

During both versions of the presentation he provides an analogy which he

attributes to Jonathan Weisberg, although he has modified it somewhat – the

original argument by Weisberg is available here. (I will discuss that argument in another article, and

link to Weisberg's argument again, so there’s no need to rush off to read it just yet!)

Hawthorne’s (2013) version goes a

little like this:

There are two cell blocks in a prison from which a prisoner is

about to be released. In one block, A,

there are 99 innocent prisoners and one guilty one. In the other block, B, there are 99 guilty

prisoners and one innocent one.

(For the purposes of the exercise we can imagine that the prison

is located in a country (or county) which is devoted to locking up a large proportion of

their populace – say a smidgen under 1,000 in every 100,000 – in order to keep

their previously thriving law and order, justice and incarceration industries

afloat. Sadly, in order to keep up the

supply to prisons, those at the front end have now resorted to processing

people for such crimes as “walking on the cracks in the pavement”, “possession

of an offensive wife”, “smelling of foreign food” and “looking at me in a funny

way” (thanks largely to this hypothetical country’s version of Constable Savage). Fortunately, there still sufficient disparity

in wealth to drive the level of crime needed to ensure that about 50% of those

in prison are bona fide criminals.)

The decision as to which prisoner is to be released is to be made

by one of two officials, Mr Random, who will just pick a prisoner at random

(irrespective of whether he or she is guilty or not), and Miss Justice, who

will only release a prisoner if that prisoner is innocent.

What we don’t know is who makes the decision to release the

prisoner, and we don’t know any details regarding how they make their

decisions, beyond what has already been revealed.

Say that the prisoner who is released was one of those put away

for “wearing a loud shirt in a built-up area in the early hours of the morning”

(in other words he is guilty of no more than fashion crime). What can we say about the likelihood that Mr

Random or Miss Justice released the prisoner?

If we know nothing other than that the

prisoner is (relatively) innocent, we could assume that it’s 66% likely that Miss

Justice was in charge of the release, because she doesn’t release the guilty,

so innocents will be released by her 100% of the time and only 50% of the time

by Mr Random.

But what if we also know what cell

block the prisoner came from? Say that

the prisoner came from cell block B, in which there was only one innocent

prisoner? This fact, according to

Hawthorne, makes it even more likely that the person in charge of the release

was Miss Justice, because there is a 1% chance of Mr Random selecting the

innocent from that cell block, if he were in charge, but a 100% chance if Miss

Justice was responsible.

While Hawthorne’s conclusion does

seem eminently reasonable when he’s presenting the argument, there are at least

two hidden assumptions. Hawthorne

doesn’t hide one of the assumptions in question, explaining it some depth. Before I get onto that, however, I want to

ram home Hawthorne’s variant of the analogy a little.

Innocence is analogous to life (or

perhaps “life-permittingness”) and Miss Justice is analogous to a designer with

a preference (in this case, a preference for innocence) who is standing in for a

god with a life fixation while Mr Random is a reification of blind luck or

chance.

The argument then goes that if

“life-permittingness” is highly unlikely in the universe (à la the fine-tuning

argument), then the likelihood of a designer of the universe who prefers

universes with life (perhaps because life is necessary for something the

designer is really aiming for, almost invariably presumed to be intelligence)

becomes correspondingly high. Therefore

god.

However, as suggested, there are at

least two hidden assumptions.

We don’t know how the prisoner was

selected and in order to get the figures that Hawthorne reaches, we have to assume

that:

a.

it is equally likely, for any given release, that Miss Justice or

Mr Random should be in charge, and

b.

when Miss Justice is in charge, she first selects the cell block

at random, and then somehow selects an innocent prisoner.

Hawthorne spends quite some time to

try to convince us that the second assumption is reasonable. (He just breezes over the first assumption

which is okay, I suppose, since he did warn us that the presentation would be

breezy.) But are either of these

assumptions reasonable in terms of the analogy?

I’d say that neither of them is

reasonable at all. I am tempted to let

the first assumption slide for the same reason that I am often willing to

concede (for the sake of the argument with a theist) a deist god – one which

lights the metaphorical fuze for the Big Bang and then is never seen or heard from

again. A universe created by such a god

that subsequently resulted in us would be indistinguishable from a universe

which, by mere happenstance, resulted in us.

But it’s worth noting that by virtue of the underlying assumption, the

hypothesis of intelligent design is given an initial boost to a likelihood of 50%.

The second assumption, however,

needs some attention. Hawthorne

criticises Weisberg for suggesting that there is “no reason” to believe that

Miss Justice would not use the selection method assumed in his (Hawthorne’s)

version of the analogy. Weisberg writes:

“We have no reason to think the judge cares where the pardoned prisoner is

housed, but as it happens there are (99) innocent prisoners in cell block A,

and only 1 in cell block B.” Note that

Weisberg used a figure of 9 innocents in cell block A, but I am going to stick

with Hawthornesque figures. Hawthorne

suggests that even if we are only 5% certain that Miss Justice will use that assumed

method, then we will have a significant certainty that she selected the

prisoner to be released – if the prisoner was both innocent and from cell block

B.

There are two issues. The first is that the figures are possibly

not as impressive as they are made out to be and the second is that there are

reasons why Miss Justice would not use the assumed method (and I believe that

this fact is inherent in Weisberg’s argument, but it has been overlooked by

Hawthorne).

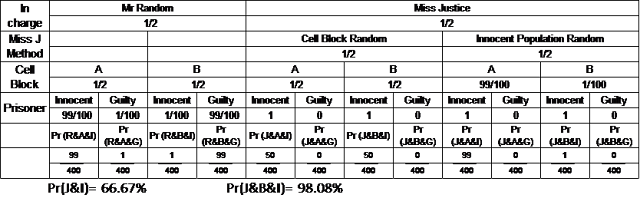

First the figures. On the basis that an innocent is released,

given some apparently trivial assumptions, we can reach a conclusion that it is

66.7% likely that Miss Justice was in charge of the decision:

Pr(J|I) = ( Pr(J&A&I) + Pr(J&B&I) )

/ ( Pr(J&A&I) + Pr(J&B&I) + Pr(R&A&I) +

Pr(R&B&I) )

= (100/400 + 100/400) / (100/400 +

100/400 + 99/400 + 1/400)

= 200/300

= 66.7%

If we know that the prisoner is

from cell block B, as well as being innocent, we use a different equation:

Pr(J|B&I) = ( Pr(J&B&I) )

/ ( Pr(J&B&I) + Pr(R&B&I) )

= (100/400)

/ (100/400 + 1/400)

= 100/101

= 99.01%

This looks good, but it is

contingent on a base likelihood (prior) of 50% for Miss Justice being in charge

(as well as the assumption of a 50-50 toss on which cell block to select a

prisoner from). Let’s assume instead

that it is somewhat less likely that she is in charge*:

Pr(J|I) = ( Pr(J&A&I) + Pr(J&B&I) )

/ ( Pr(J&A&I) + Pr(J&B&I) + Pr(R&A&I) +

Pr(R&B&I) )

= (100/20000 + 100/20000) / (100/20000 + 100/20000 + 9801/20000 + 99/20000)

= 200/10100

= 1.98%

Pr(J|B&I) = ( Pr(J&B&I) )

/ ( Pr(J&B&I) + Pr(R&B&I) )

=

(100/2000) / (100/2000 + 9/2000)

= 100/109

= 50.25%

This result could easily impress Plantinga, who

thinks that “about half” suffices as proof for his god, but it’s merely a

coincidence. If we make the base

likelihood of Miss Justice being in charge 1/1000, while holding everything

else constant, then the Pr(J|B&I) figure falls away to less than 10%. Make it 1 in a million and we get one

hundredth of one per cent.

This might, perhaps, seem

unreasonable on my part – but one of the arguments that Hawthorne is likely to

mount in his defence is that there is “no reason” to assume that the base

likelihood of Miss Justice being in charge (or god being the intelligent

designer) is as low as, or lower, than 1/100.

But Hawthorne himself suggests that we shouldn’t use “no reason”

arguments. (If he has other arguments,

I’ll leave it to him to present them.)

From my perspective it seems like

Hawthorne is trying to bump the likelihood of god as designer to levels that

are statistically significant, by means of assuming a pre-existing likelihood

that is already reasonably high. It

occurs to me that this is a form of fine-tuning of its own, may be

meta-fine-tuning – given that the supporting analysis favouring the idea that

the fine-tuning argument might be significant must be fine-tuned within a

narrowish band.

Now that we have touched again on

the issue of “no reason”, let’s move towards a consideration as to whether

there truly is no reason to believe that Miss Justice might choose a particular

method of selecting prisoners for release.

Hawthorne does concede that it is possible that Miss Justice might use a

different approach than selecting a cell block at random and then using some criteria

to select a prisoner for release from that cell block. He suggests considering a 50-50 chance that

she selects a prisoner at random from the population of 100 innocent prisoners.

Let’s do that:

Using the same processes as above,

we arrive at a Pr(J|I) of 66.7% again, but a Pr(J|B&I) of 98.08%, which

isn’t a huge drop below 99%. But the

consequences of a lower base likelihood of Miss Justice being in charge are interesting:

Now Pr(J|B&I), the figure we

are truly interested in, has dropped to 34.00%.

If we make the likelihood of Miss Justice being in charge 1/1000, we get

a Pr(J|B&I) of less than 5%.

Hawthorne, however, suggested that

we might only be 5% confident that his preferred method was being used, so:

Pr(J|I) does not shift from 66.7%,

but Pr(J|B&I) has dropped a little.

When we look at a less likely Miss Justice, this effect is amplified:

I would argue that we should not be

even 5% confident that Miss Justice would use the method that Hawthorne prefers. And I believe that this argument carries

across into the scenario that this analogy is being applied to.

Consider what Miss Justice

represents. She is order being compared against

random chaos. She doesn’t just select a

prisoner for release at random, she has rules that she follows, she’s rational,

she thinks, she’s intelligent. However,

what Hawthorne is trying to have us believe is that she will also be

inconsistent, she will only be semi-rational.

Not only will she allow herself to be chosen at random (despite the fact

that her colleague is known to release guilty prisoners, else the whole

scenario falls apart), but she will also allow a random element to enter her

considerations. This is not an analogy

for intelligent design, this is at best an analogy for semi-intelligent,

or capricious design – by an agent that is not fully in control.

We need to look more closely at the

possible methods that Miss Justice might use to make a choice. She might:

select an innocent prisoner at random (Ran)

select the most innocent prisoner (MIn)

select the most recently arrived innocent prisoner (MRe)

select the innocent prisoner who has served the longest (Lon)

select an innocent prisoner based on some other relevant factor

(like ill health, age or frailty) (ReF)

select an innocent prisoner based on an irrelevant factor (like

attractiveness, race or wealth) (IrF)

randomly select a cell block

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

select the cell block with most innocents

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

select the cell block with fewest innocents

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

select the cell block based on some other relevant factor (say

worst living conditions)

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

select the cell block based on some irrelevant factor (say the

results of the latest football game)

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

randomly select a grouping based on some criterion other than cell

block (perhaps by race, or gender, or hair colour, or height)

then Ran

then MIn

then MRe

then Lon

then IrF

then ReF

select a grouping with most innocents

… and so on

I have no intention of crunching

the numbers associated with all these options.

What I can say instead is that it begins to look unlikely that we can

justifiably claim that it’s 50-50 as to whether Miss Justice uses the selection

method preferred by Hawthorne. We can’t

really get a quantitative grip on the likelihoods though because we don’t know

how many other relevant and irrelevant factors might exist and how likely they

are to sway Miss Justice. (An argument that could be mounted here is that other

than innocent-guilt and cell block, the prisoners should be considered as

homogenous but I suspect that this will negatively affect the utility of the

analogy for design theorists.)

What we can do instead is get a qualitative

grip, based on what Miss Justice is supposed to be representing. She’s all about justice and rules –

specifically not about random chance – and if so, it is reasonable to assume

that she will reject any methodology that incorporates random chance or

irrelevant factors. Within the scenario

Miss Justice is not responsible for the distribution of prisoners and therefore

that distribution can be considered to be random – since she has no control

over which of the innocent prisoners is in cell block B. So, any consideration which does not take

into account the entire population of innocent prisoners will incorporate

random chance, and will be rejected as a feature within a selection method. (In terms of the analogy, this is equivalent

to suggesting that the intelligent designer does not play dice, that the notion

of omniscience is not abandoned – because if a being is omniscient, it follows

that the results of its actions cannot be random.)

This leaves us with Miss Justice

using a method that ensures that she selects an innocent prisoner based on some

relevant criterion. We

don’t know what that criterion is, but we don’t need to, since no matter what

she uses, the likelihood that, given the opportunity, she will pick a prisoner

from cell block B remains the same – assuming only that prisoners are

distributed randomly (at the hands of some other prison official). So, we can now crunch some numbers again:

If anyone wants to play with the

spreadsheet that generated these tables, it is available here. Because formatting can get messy when

fractions are used, I’ve used percentages in this version. I’ve also introduced colours to make things a

little easier – the cells with a yellow background are the only ones that you

can modify, but you can look at the equations in the other cells if you want to

check my work. (You can even fiddle with

the proportions of guilty and innocent prisoners, and put in figures that match

Weisberg’s, if that tickles your fancy.)

What the analysis tells us is that,

unless you make an unreasonable assumption about Miss Justice, the fact that it

is unlikely that an innocent prisoner should have been released from cell block

B does not provide us with any additional confidence that Miss Justice was

involved in the decision making process.

Similarly, the notion that the

universe appears to be fine-tuned for life does not provide any additional support

for the argument that there is an intelligent designer with a preference for

life. Any arguments from fine-tuning for

(intelligent) life are no better than an argument from the existence of

(intelligent) life. And all of us, at

least those of us who are sufficiently intelligent, have always been aware of

the existence of (intelligent) life.

---

I’d be overjoyed if I were able to

say that this result is precisely the result that Jonathan Weisman arrives at

in the referenced article. Sadly however,

his argument is somewhat different, the analogy is used differently and he eventually

argues that the situation is actually worse for the design

theorist that I have indicated so far.

The silver lining is that I am

pretty sure that Weisberg’s argument cleaves rather close to the one I want to

make about the different options for making life that a god might have. I’ll get to that in the continuation (in Weisberg's Prisoners).

(Weisberg does reach the same, or a

similar, conclusion but does so merely in passing without addressing any

potential criticism of the sort levelled by Hawthorne and, in doing so, he

calls on “divine indifference” which incorporates an element of random chance.)

---

* Please note that in his 2013 presentation, Hawthorne said that a likelihood of god at 1/100 is “pretty high”, so I don’t feel that am being unreasonable when I look at a base likelihood of 1/100 with respect to Miss Justice being in charge.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Feel free to comment, but play nicely!

Sadly, the unremitting attention of a spambot means you may have to verify your humanity.